Restoring the Land with Flames: The Ecological and Cultural Legacy of Prescribed Burns

A hazy cloud shifts through the trees, and from the billow of smoke emerges a human, hardly recognizable, adorned in an eerily bright yellow bodysuit, a dripping torch in hand, spewing flames, leaving a trail of destruction in their wake.

While the smoke may appear dramatic and the people unusual, prescribed burns are a long-standing restoration practice that the Natural Lands has implemented since 2001 (Braker). The Natural Lands encompass over 430 acres surrounding St. Olaf College (“About the Natural Lands”). Home to hundreds of species, native and invasive, across the forests, prairies, and wetlands, these areas are managed through a variety of techniques, including prescribed burns.

Fig. 1. Abby Sikora, Carleton Arboretum, 4 Nov. 2025.

Prescribed burns on campus maintain healthy, regenerative ecosystems when carried out in cycles that allow the landscape to rest for several years between burns. As fire moves across a prairie, it removes built-up dead grasses, returns nutrients to the soil, awakens dormant seeds, and revitalizes the landscape. Grasses often grow back thicker and more nutrient-rich, attracting a wider range of wildlife (“Creating a Relationship with Fire”). Prescribed fire also reduces forest density, increases plant diversity, decreases tree competition, improves wildlife habitat, helps control invasive species, and supports species that rely on fire-stimulated seed germination, such as jack pines whose cones require heat to open and release seeds (Quigley et al.).

Prescribed burns are a conservation method with a history predating the colonization of the West. Indigenous people have used fire to modify eco-cultural systems for millennia (Eisenberg et al.; National Park Service). Unlike the popular ideology of the natural landscape being a pristine wilderness untouched by human hand, the United States has been cultivated with fire by Native Americans for thousands of years before Euro-American colonization. Traditional ecological knowledge of burns promotes ecosystem structure, modifying vegetation to improve ecosystem productivity and manipulate herbivore herds (Eisenberg et al.). Indigenous and Aboriginal purposes for the burns include promoting ecological diversity, burning encroaching woody vegetation to preserve the composition of open prairies, reducing the risk of serious wildfires, and enhancing harvesting resources to support specific vegetation used for food and medicine. Burns remove overgrown undergrowth, making the woods cleaner and easier to travel through. They were also used in the North American grasslands as a part of herding bison to hunt by removing bison’s grazing forage in particular areas (Roos et al.). Later, those burned areas provided a rejuvenated grazing and, therefore, hunting location.

Even before intense Euro-American colonization, lifestyle changes influenced traditional burning habits. CKST exemplifies these changes through the study of the Salish and Pend d’Oreille people of the northwestern U.S. The introduction of diseases such as smallpox as early as the 1500s swept through the Northwest and decimated tribal populations. Horses, which became more common around the 1700s, and the increase in firearms meant that conflicts traveled faster and further into the territory of enemy tribes, bringing new levels of power with the increased conflict and deadliness of warfare with firearms. Population losses from warfare and epidemics likely affected the use of fire by reducing the number of knowledgeable and able-bodied people available to manage the burning. It also made it far more difficult for tribes to resist incursions into their territories by fur traders as colonization increased (CKST “History”). These changes incrementally led to native marginalization, including the traditional use of fire.

As disease and colonization wiped out Indigenous populations, fire management changed. It is well known that Native American populations declined between 1492 and 1900, instigated by the European colonization of the Americas (Liebmann et al.). This depopulation resulted in more frequent occurrences of extensive surface fires between 1640 and 1900 (Liebmann et al.). European colonizers increased fire suppression, which later intensified in the 20th century as land-management agencies enforced new and often stricter policies.

Without frequent burns, organic matter accumulates, putting forests at heightened risk of destructive, rampant wildfire. Fire suppression, climate change, and urban development have all contributed to the uncontrolled fires that so frequently headline the news. The Great Fire of 1910, one of the largest wildfires in U.S. history, illustrates the consequences of fire suppression and neglecting land management. While the blaze was sparked by a brief period of drought and heat followed by summer lightning storms, it was fueled by the removal of Indigenous fire practices. The buildup of organic matter and the heavy logging of the Bitterroot Valley, a region greatly impacted by the 1910 fire, further intensified the devastation. Old-growth trees, like ponderosa pine, which typically survive fires and contribute to a more “fireproof” forest, have been largely removed (CKST). Logging transformed the landscape from old forests into a very different and far more fire-prone ecosystem.

Fig. 2. Kendra Fallon, Boise State News, 2012.

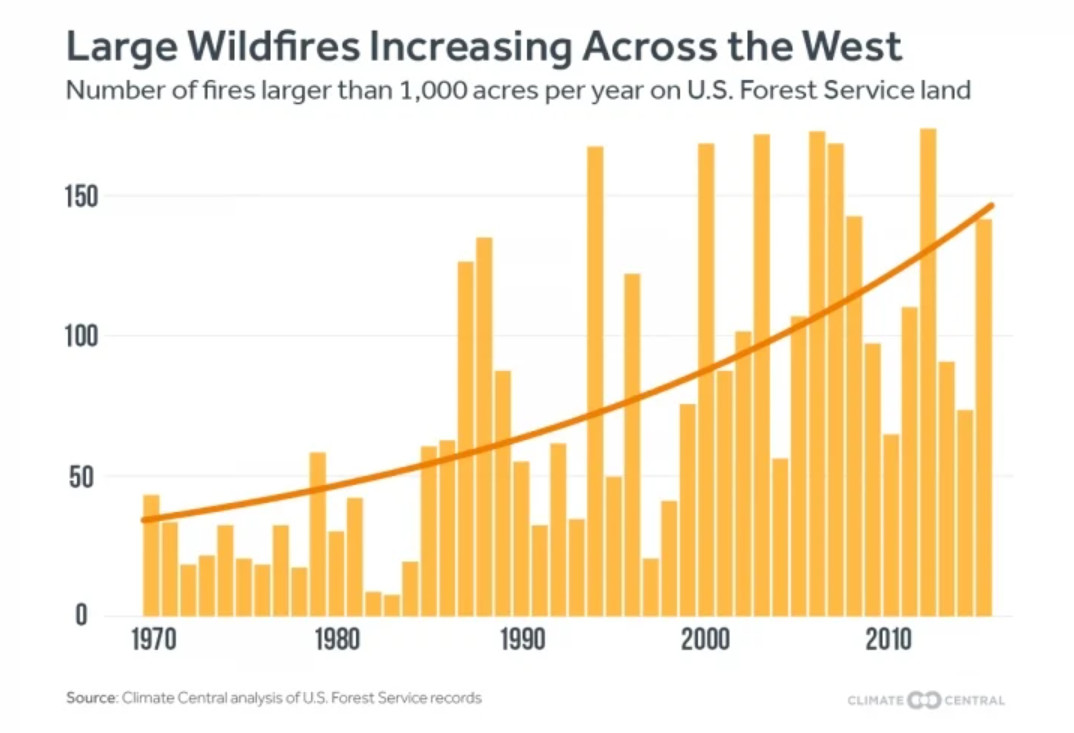

Rising temperatures, extended droughts, invasive species, and longer fire seasons are all impacts of climate change. Although wildfires are a part of the natural ecosystem cycle, the intensity and frequency have been increasing at an alarming rate in recent decades. Studies even indicate that climate change through anthropogenic warming is the main driver of the increase in fires in the western United States (Zhuang et al.).

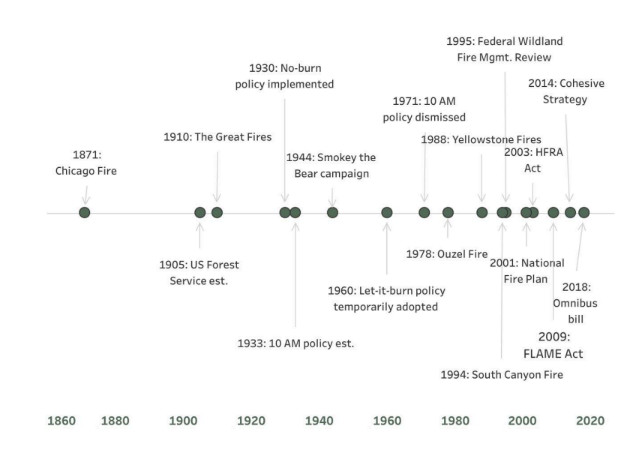

After the 1910 fire and a series of catastrophic wildfires in the early 1900s, the predominant view of fire in forest ecology and land management was nearly unanimous, with the consensus that any forest fire, intentional or not, was entirely destructive and even morally evil (CKST). The U.S. Forest Service and other federal agencies created policies of suppression to protect communities and natural resources from wildfires. While some foresters acknowledged that fire could be beneficial, agencies worried that communicating fire as sometimes good and sometimes bad would confuse the public. As a result, the Forest Service maintained a policy of aggressive wildfire suppression, exemplified by the 1935 “10 a.m. policy,” which required that all fires be under control by 10:00 a.m. the following day (Donovan and Brown, 75). This approach remained in place until the 1970s, when the long-term impacts of such vigorous fire suppression began to surface.

Fig. 3. Analysis of U.S. Forest Service Records, Climate Central

Wildfire suppression is effective 95% to 98% of the time, but this effectiveness leads to long-term fuel accumulation and, ultimately, to more severe and ecologically disruptive fires (Calkin et al.). Remarkably, the 3% of fires that escape suppression are responsible for 97% of the total area burned (Calkin et al.). This is known as the “wildfire paradox,” showing that eliminating wildfires is neither ecologically nor physically achievable (Calkin et al.). To address this, fire-management goals must shift from reactive suppression to proactive strategies that emphasize ecological preparedness, including prescribed burns, conservation, and public policies that help communities understand and plan for the inevitability of fire.

Fig. 4. Kimiko Barrett. Burns and policies timeline. 27 April 2020.

By the 1980s, changes in policies allowed many natural fires to burn on federal wildland. Initiated in 2000, the National Fire Plan (NFP) was developed following an intense fire season, with new approaches to responding to severe wildland fires, impacts on communities, and sufficient firefighting capacity for the future (Donovan and Brown, 75). The NFP addressed firefighting, rehabilitation, hazardous fuel reduction, community assistance, and accountability. An effect of this was the implementation of prescribed fire, mechanical thinning, herbicides, grazing, and other methods to reduce hazardous fuels. The 2003 Healthy Forests Initiative and the Healthy Forests Restoration Act focused on appropriately equipping land managers with additional tools to achieve long-term objectives in reducing fuels through prescribed burns and restoring fire-adapted ecosystems (Donovan and Brown, 75).

As traditional ecological knowledge resurfaces within Western land-management practices, fire has reclaimed its role as an essential tool for restoring and sustaining ecosystems. Today, the rhythmic cycle of prescribed burns at St. Olaf reflects this renewed understanding of fire’s power to sustain and regenerate the land.

Suggested Reading and Sources

You must be logged in to post a comment.