“As with many good ideas, serendipity played a part in the development of the Natural Lands. This involved a student project, the location siting of a new dormitory, the destruction of a cave, alumni support, and the federal government.”

Gene Bakko, First Curator of the Natural Lands

This page details the chronological history of the Natural Lands along with discussing different parcels of land and their restoration years. To maximize comprehension, it can be helpful to refer to the Natural Lands map while going through this page.

1980’s

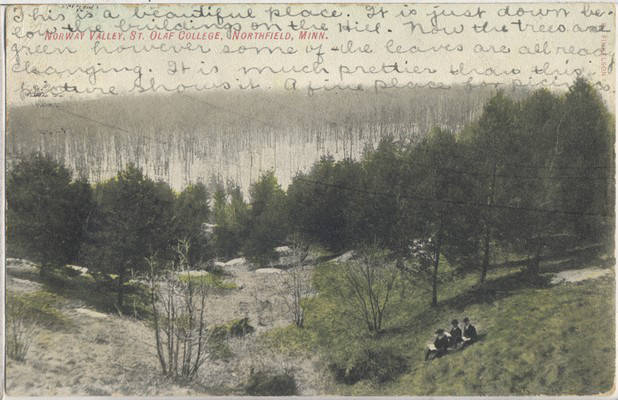

The first seed of the Natural Lands began to germinate over 40 years ago when in 1980, David Wedin (‘81) came to then professor of biology Gene Bakko with a semester project idea titled ‘St. Olaf as a Nature Area’. Under Bakko’s direction, Wedin identified all existing natural areas on campus and examined college-owned property that could be restored to native habitats. They discovered that in addition to the campus itself, the college owned all the farmland to the west and north of campus. At that time (1980) the only major “natural areas” were Norway Valley, the woods below Ellingson, and the woods behind Hoyme.

Wedin then asked about doing a tree and prairie planting on campus, and Bakko set him up with 50 native tree seedlings and approximately 1/3 acre worth of native grass and forb seed. These trees and seeds were planted in the southwest corner of what is now labeled the Spring 2002 prairie restoration, marking 1981 as the first year of contemporary habitat restoration on St. Olaf property.

Five years later, the construction of Ytterboe Hall served as a further catalyst for fostering interest in natural areas. In 1986, several science faculty learned that Ytterboe was going to be constructed in the heart of what was then known as Hoyme Woods, greatly fragmenting the habitat and eliminating all but a few mature trees in the area. Bakko made an appointment with Melvin George, the newly appointed President of the College at the time, to address the issue. President George recognized the problem, and upon meeting with architects, the planned location of Ytterboe was shifted to where it stands today. This new location greatly reduced the number of trees that had to be cut down. This issue also alerted President George to the need for additional awareness of environmental affairs on campus and led to the formation of the Environmental Concerns Committee.

At about the same time, the college bulldozed the hazardous cave site below Thorson and Ellingson, leaving behind a hill of exposed soil. Some of the smaller tree saplings that were to be removed due to the placement of Ytterboe, were replanted at the exposed cave fill-in site.

The Conservation Reserve Program

The final impetus for restoring natural areas on college property was the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), a US Department of Agriculture program that paid landowners to take agricultural land out of production and convert it to vegetative cover to reduce erosion and farm commodity surpluses while improving water and wildlife habitat quality. Through this program, St. Olaf College received $75/acre/year for 10 years, the rate of rented farmland at the time, allowing the college not to lose money. In 1988, 23 acres of land were enrolled and 20-30 native tree species were planted, with approximately 500 trees per acre. These areas included the 1988 and 1989 forests north of Baseball Pond, as well as the 1990 tree plantings west of Kittelsby and Hoyme dorms (see map for details).

While approximately 21 of the 23 acres were planted as forest, the remaining acres were devoted to our first prairie planting. Encompassing the western portion of the 1988 planting, the former corn field was disked in the spring of 1989 to inhibit weed growth. Seed was then hand-spread across the field, followed by a pickup truck dragging a section of chain link fence to increase the seed contact with the soil and improve germination. For the following two years, the prairie was cut at a height of 18 inches to prevent annual weeds from going to seed. Three years post-seeding, the prairie was burned and subsequently burned every 3-5 years thereafter.

1990’s

In addition to the 1988 and 1989 forest plantings, the 23 acres enrolled in the CRP also included the two 1990 tree plantings which contain the Forest Restoration Loop trails. Planting 500/trees per acre, approximately 10,000 native hardwoods were planted across the 20+ CRP acres devoted to forest. The Natural Lands became a source of research early in its founding, with some of the tree seedlings being protected with tree tubes to see how this would affect growth and survival rates.

The two 1992 tree plantings, located west of Cedar Avenue, were originally mowed grass as opposed to agriculture like most of the Natural Lands. The restoration area to the north was planted with native nursery saplings from Knecht Nursery, which is located directly south of campus and founded by St. Olaf Alumnus Leif Knecht (’75). Knecht was very helpful with future plantings as well. The smaller restoration located just north of the Ellingson Woods Trail was hand-planted with seedlings.

In 1993, the first of the two conifer plantings was established. The 1993 6-acre planting was part of a larger 51-acre parcel that the College enrolled into the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) Conservation Easement program, which also resulted in the restoration of Big Pond and the 1993 prairie (described later). While conifers are not native to southern Minnesota, this parcel and the later 1999 planting represent the conifers of northern Minnesota for educational and research purposes. Eight species were included in the plantings, with white pine (Pinus strobus), jack pine (Pinus banksiana), and red pine (Pinus resinosa) making up a majority of the planted trees. Other species include balsam fir (Abies balsamea), white spruce (Picea glauca), black spruce (Picea mariana), white cedar (Thuja occidentalis), and tamarack (Larix laricina).

In this same year, a major expansion of prairie occurred, primarily about 50 acres surrounding what is now Big Pond. This is the same year in which the Bluebird Trail was established, emphasizing the conservation efforts happening on the Natural Lands.

The next expansion of the Natural Lands came in 1993. For years, the college had dumped construction and excavated material at the northwest corner of the campus, this area becoming known as the Rubble Pile. As the Natural Lands grew, this pile needed to be converted to a more natural habitat. Due to the dumped materials, there were additional challenges with the location. The rubble had to be pushed from the top of the pile over the edges, turning the steep slope into a more gradual one. Then the entire area was covered with soil and planted with native species. Campus Drive, the access road connecting the Skogland parking lot to the old compost facility, was constructed soon after. Both sides of the road, after disking, were planted with native grasses. This has resulted in the 2011 prairie planting and the Campus Drive roadside being great locations for grass seed collection.

In 1998, an additional 30 acres of land was put into the CRP. A majority of the planting of this field, located west of the Windmill Trail, was done in 1998, with further planting continuing through 2004 including the expansion of the conifer forest.

2000’s

In 2000, both The Henry and Agnes Nelson Family Endowment and the Morton and Thelma Egeland Endowment for Environmental Science were created, providing essential funding to continue environmental stewardship in the Natural Lands (see the benefactors section to learn more). About 4 acres of the 1998 CRP land was devoted to direct seeding. Performed in 2001, this was a relatively new method of establishing large tree plantings. The seed, provided primarily by the DNR, was hand-spread over disturbed soil, followed by the seed being worked in by lightly disking the field with a tractor. This method, while new, grew in popularity and was further used for the 2002, 2003, and 2005 tree seedings, which total 32 acres and extend toward Highway 19 as it allowed for relatively quick planting, in addition to overwhelming any seed-eating animals with sheer quantity of seed, ensuring the survival of a large portion of plants.

In 2001, the US Fish and Wildlife Department offered another permanent easement program for a limited time. St. Olaf took advantage and received a contract for an additional 100 acres which extended the prairie restorations north to North Ave and west to Eaves Ave, receiving $2,500 per acre. This grant money enabled the project, which would’ve been cost-prohibitive at the time, as prairie restorations cost over $1000 per acre. These parcels were planted between 2002 and 2004. The Spring 1998 prairie restoration was originally thought to be the limit to the natural habitat restoration program, and so to add diversity, a small oak forest was planted in 1993 on the western 7 acres along with timothy grass as ground cover. When the Natural Lands was extended further, a small forest surrounded by further prairie wouldn’t have made much sense compared to continuous prairie. Thus, many of the planted seedlings were removed save for a select few bur (Quercus macrocarpa) and red oak (Q. rubra), which established a savanna-like area. The domestic grass species, which would’ve died off as the canopy closed, instead grew with the additional sunlight. The grass had to be mowed and burned, followed by the planting of native prairie species in 2003.

On April 27, 2001, a wildfire erupted in the Natural Lands. It was the Saturday night of the President’s Ball, celebrating the inauguration of the new St. Olaf President, Chris Thomforde. Fireworks were used in the celebration, being set off near Skoglund. Embers ended up reaching the ground, igniting the 1993 prairie planting north of the Big Pond loop. Multiple 911 calls were made. When the firetrucks arrived, the weight of the vehicles in addition to the water they carried resulted in them getting stuck in the field. The fire eventually burned itself out, being contained by the trail to the south, agricultural land to the north and west, and Campus Drive to the east. The firetrucks were later towed out by tractors, leaving deep ruts in soil and several destroyed bluebird boxes in their wake.

In 2007, a natural gas pipeline was routed through the Natural Lands, influencing the location of the Windmill Trail. The saplings on either side are a part of the 2002 tree seeding.

In 2009, the Heath Creek section of the Natural Lands began to see its first of several restorations when a parcel of agricultural land devoted to corn production was restored to deciduous forest. In the last growing season before restoration, the field was converted to soybean agriculture to allow nitrogen levels to increase and remnant biomass from previous years of corn to degrade. Following harvest, the invasive Siberian elm trees (Ulmus pumila) surrounding the planting were girdled to inhibit seed spread into the restoration; This had limited success, likely due to the seeds already being established in the soil. Direct seeding followed, along with a light disking to increase germination and decrease predation. Two rounds of mowing were performed in the following years to help control annual weeds including lamb’s-quarters (Chenopodium album) and ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia). Further management included the treating of creeping (Canada) thistle (Cirsium arvense) populations as they appeared, as well as stump-treating buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica) populations around the edges of the planting.

In the same year, Professor Kathy Shea took over as Curator of Natural Lands upon the retirement of Gene Bakko. Kathy had been involved with the Natural Lands since its inception, especially involving the restoration of woodlands.

2010’s

The 2017 direct seeding restoration in Heath Creek used very similar methods to the 2009 restoration, save for this restoration being the first to include a climate-adapted planting. The species list for this restoration included Kentucky coffee tree (Gymnocladus dioicus) and swamp white oak (Quercus bicolor) among many others. These species will help mitigate the effects of climate change on the plots as they are proven to be resilient to warmer temperatures. In essence, planting these species facilitates the northern movement of populations that will happen naturally over time due to the changing climate conditions.

2020’s

In 2021, Wes Braker (’18) was hired as Natural Lands Manager, thanks to another generous gift from Donald Nelson. Professor Charles Umbanhowar took over as Curator of Natural Lands that same year with the impending retirement of Kathy Shea. The position title was redesignated as Director of Natural Lands. Charles and Wes have considerable Natural Lands experience and expertise in restoration ecology. (See Natural Lands Faculty and Staff)

In October 2021, St. Olaf College received a generous donation of approximately 30 acres of land from Post Consumer Brands. This land, which was directly adjacent to the existing Heath Creek forest owned by the college, was, in turn, designated a Natural Lands area. In 2022, the outer edge of the land that was previously used for agriculture was seeded, using similar methods of previous Heath Creek restorations.

In 2023, a large portion of the farmland devoted to James Farm (9 acres) was converted to prairie, the first proper prairie restoration in over 20 years. This was the last piece of agricultural land immediately adjacent to the Natural Lands. The land has been under a no-till regime for the past 2 decades, allowing soil health and quality to improve compared to traditional agriculture. Following the fall harvest of soybeans, two restoration-oriented research plots were established: one to examine little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) and another for wood betony (Pedicularis canadensis). The first order of business was the burning of the small strip of land between the field and the nearby paved bike trail to remove the existing non-native grass species. The tile lines, an underground water removal system commonly used in agriculture, were removed via excavation. This will likely result in the south-eastern portion of the restoration and South Eaves pond becoming wetter. Over 125 native prairie species were then hand-spread over the land. At least 30 of these species did not exist elsewhere in the restored prairie. For reference, some of the first prairie restorations of the Natural Lands used only 35-45 species of seed total, while remnant prairies can have over 300 plant species per square mile.

In 2026, the remainder of the land received from Post Consumer Brands will be restored to deciduous forest.

You must be logged in to post a comment.