Project Description

The Musical Geography sequence of three DHH-CURI (Collaborative Undergraduate Research and Inquiry) projects and a DUR (Directed Undergraduate Research) course, part of a larger ongoing research agenda, asks the question “how can mapping change the way we think about music history?” The projects explore the intersections of space, time, and sound through map-centered investigations of music and musicians.

Music scholars link time and place as a means to help contextualize chronological developments in music with the cultural and aesthetic constraints of a particular geographic locale – but such connections between time and place can be difficult for students (and even other scholars) to perceive. This sequence of projects explores some of the many ways in which linking time and place visually can enrich our understanding of music history.

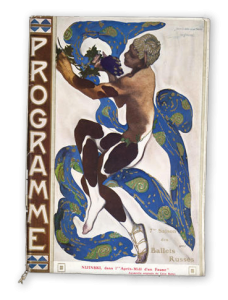

The first of the projects, in summer 2015, focused on researching and visualizing the musical geography of 1924 Paris, exploring new ways to represent and reconstruct music history. The project sought to evoke the times, tells stories, and brings lost sounds to life in a way that can inform present-day discussions of music’s role in society. Paris in 1924 provides an attractive frame for this kind of work because its musical life was unusually rich and unusually well-documented.

Successive Musical Geography projects in the summers of 2016 and 2017 incorporated increasingly broader chronological and geographical scope. While the 1920s Paris project rendered the city’s soundscape through the model of thick description, subsequent projects became more attuned to historical trends and changes in performance practices or repertories over time as well as over larger geographies. In all three phases, students conducted intensive primary and secondary source research to collect relevant data, including exact dates, locations, repertory, and documentary evidence for a variety of musical events.  This involved research within digital and physical archives for manuscripts, newspapers, memoirs, correspondence, books, advertisements, recordings, and other evidence of music-making.

This involved research within digital and physical archives for manuscripts, newspapers, memoirs, correspondence, books, advertisements, recordings, and other evidence of music-making.

Students then organized and analyzed the data and determined how best to present it on a series of interactive maps, contextualizing the primary sources and maps through digital storytelling modules on the Musical Geography website.

In the third phase, there was an additional focus on organizing archival information. Students surveyed a variety of secondary sources with an eye towards critical historiography, asking how the biases and sources of each writer might change the nature and facts of the story being told. Students worked with faculty and research librarians to develop an extensive bibliography of relevant primary sources like newspapers, travel guides, correspondence, and administrative documents, which they curated and presented to the public through the project website. Students in all three phases maintained individual private research journals to help them keep track of sources and ideas, and contributed a series of blog posts to the website reflecting on the trials and tribulations of the research process.

The following student researchers contributed to the Musical Geography project

- 2015 – Katharina Biermann, Philip Claussen, Natalie Kopp, Breanna Olson

- 2016 – Emily Hynes, Stella Li, Carolyn Nuelle, Samuel Parker

- 2017 – Juliette Emmanuel, Elizabeth Lacy, Anna Perkins, Siriana Lundgren

Here is a video in which Katharina, Phillip and Natalie recount their experiences as CURI researchers.

[iframe width=”560″ height=”315″ src=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/HUp6IeL4DPI” frameborder=”0″ allow=”autoplay; encrypted-media” allowfullscreen></iframe]