Adventures in the New Humanities: Con me

This post is part of a blog series, ‘Adventures in the New Humanities,’ by Judy Kutulas, the Boldt Family Distinguished Teaching Chair in the Humanities.

I con. I’ll just come right out and admit that up front. I assume most of you know that I’m not out to swindle you, but admitting my commitment to one of St. Olaf College’s signature pedagogies: the learning communities collectively known as the Conversation Programs (known less formally as the “con” programs).

Conning has been a highlight of my time at the college, something I didn’t even know I wanted to do until I was present at the creation of the American Conversations program. Since then I’ve popped in as the occasional guest in a class, taught as the second teacher for at least seven cohorts, and twice served as the lead teacher who stays with 40 students for two years. The connections I’ve forged with co-founders, teachers, and students in the program are some of the deepest I’ve made here, personally and professionally. As History Department chair, I even got to hire a former AmCon student of mine, Ed Pompeian ’05, currently assistant professor of history at Tampa State University. Ed was only the first of three Pompeians who AmConned. Conning, like outgrown clothes and bicycles, has often been handed down from one St. Olaf student to their siblings. I believe the youngest Pompeian still regrets her failure to con.

Con programs, admittedly, aren’t for everybody, but for those who join — students and teachers — they are unforgettable teaching and learning experiences, blending traditional disciplines into deep interdisciplinary understandings of things, and building intellectual communities. They are the best of the liberal arts and often the best practitioners of the new humanities. Most of all, they are centered around something we desperately need right now: the fine art of conversation.

The Conversation Programs are the best of the liberal arts and often the best practitioners of the new humanities. Most of all, they are centered around something we desperately need right now: the fine art of conversation.

But can we converse civilly anymore, given the pandemic and a summer that highlighted the depth and tenacity of institutional racism? Can we build communities that must, by definition, be at least partially virtual? How can we incorporate the stories, lessons, and challenges of the last five or six months into our curriculum and pedagogy? Who better to ask, I figured, than the people who converse at a more professional level than the rest of us do: teachers in the Conversation Programs.

Their responses told me an awful lot about commitment. People sent me detailed descriptions of their fall semesters, invited me to their meetings, took pictures of their classes for me, and, not surprisingly, wanted to converse with me more directly. This despite a reality that any con instructor can tell you: Conversation Program classes are more work. As a con veteran, I can tell you what preceded the first day of class in any of the programs: LOTS of virtual meetings, a bit of wrangling, and some amazingly satisfying moments of brainstorming. Yet instructor passion, enthusiasm, and pride at what they are doing is hard to miss. After listening, I’m in deep regret that I will retire without conning one more time.

Running Conversation Programs when you can’t have everyone together, can’t go on field trips or abroad during Interim, and will have challenges with any civic engagement projects you undertake, is a daunting prospect. Given the current campus climate, there is great need to make sure everyone gets their say while keeping conversations productive. Conversation Programs, with their built-in learning communities that extend across at least two semesters, would seem to be places where trust can build. Yet in some crucial ways, the preconditions for those learning communities have been disturbed.

Given the current campus climate, there is great need to make sure everyone gets their say while keeping conversations productive. Conversation Programs, with their built-in learning communities that extend across at least two semesters, would seem to be places where trust can build.

Still, the Conversation Programs have a leg up on the rest of us for a number of reasons that I would summarize as committed members, more self-conscious pedagogies, long practice at managing a larger number of students than most of us encounter in a given semester, and good familiarity with technology.

Let me begin with the technology. Shared instructors, shared courses, and shared grading require technological intervention to manage. Brainstorming instructors push one another into new technological territory. Conners know where to go for answers, which, of course, is usually the Digital Scholarship Center at St. Olaf (DiSCO).

Consequently, the Conversation Programs have a long history with technologies that some of us might be struggling with right now. American Conversations students have used blogs and done podcasts and been part of the crowd-sourced Mapping Prejudice study of restricted covenants in Minneapolis, just as Asian Con students have explored parts of Asia before visiting there thanks to virtual reality. Several of the Conversation Programs rely on portfolios. Second-year AmConners have already made flip-grids this term. I had to google flip-grid to find out what it even was.

So, while the rest of us might be slightly fumbling in our attempts to create a Moodle forum or use WordPress, those cunning conning profs are flip-gridding and jamboard-ing and having groups of students Zoom-perform Greek tragedies. Talk about classical studies merged with 21st-century technology!

The second-year students and profs of AmCon and Great Con have an advantage the rest of us might envy just now: they already know one another and also have experienced remote teaching together, so know what works and what doesn’t with specific classes. Speaking from experience, I know that the first day of year two of AmCon, and I assume Great Con, is one of the best days of all, a reunion with people you’ve come to cherish. Everyone feels the warm glow of familiarity as people share their summer jobs, and once in the case of Associate Professor of History Eric Fure-Slocum, news that he had purchased a new pair of khakis over the summer. All that coziness, of course, was diminished by distance this year, but by all reports, it felt good to be back and to already know names without having to rely on the Zoom screen names.

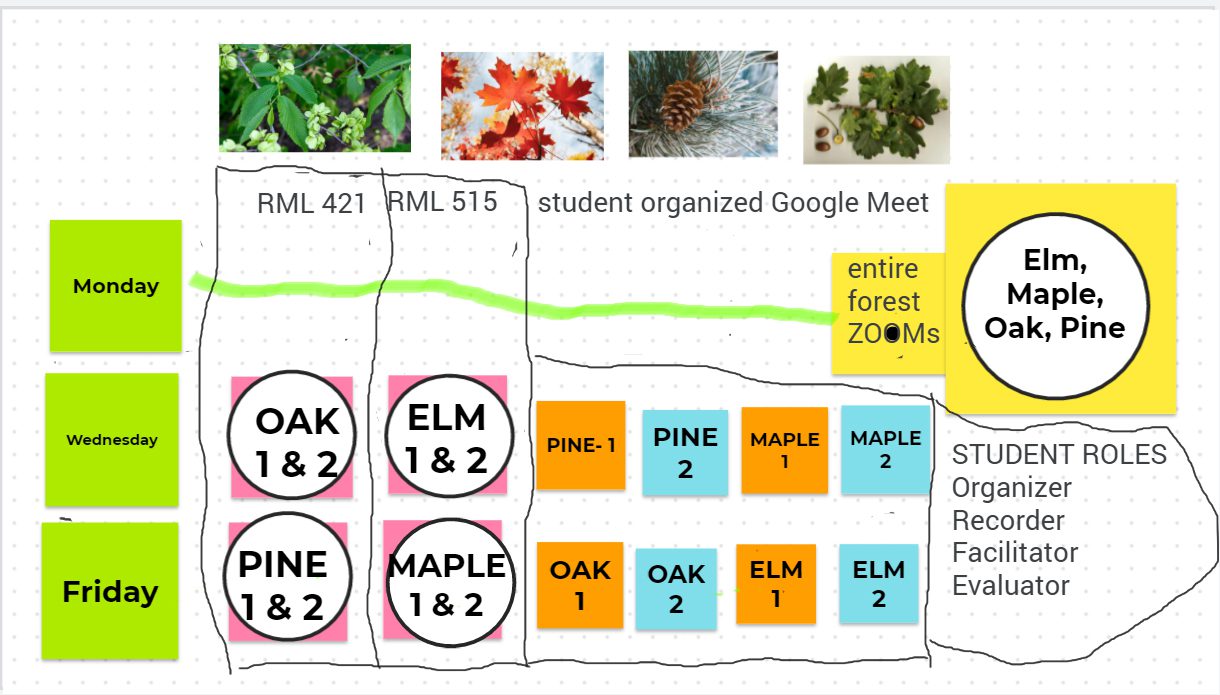

The comfort, safety, and trust built since day one of their St. Olaf experience in learning communities compensates for the fragmentation of the hybrid class. Sections and plenaries — bigger and smaller groups — are second nature to members of these programs, as, for their instructors, is managing all the transitioning. Conversation Programs have that whole big-group/small-group thing down pat, so all that was left, as Professor of English Mary Titus said of her and Harold Dittmanson Distinguished Professor of Religion DeAne Lagerquist’s second-year AmCon group, was picking the names for their hybrid small groups. They went with trees.

Conversation Programs wouldn’t be worth their salt if the realities of today didn’t just creep into their content, but roar in there. The Public Affairs Conversation (PACON) will be considering pandemic ethics by sampling the Institute for Freedom and Community’s fall event series, “The Presidential Election and a Nation in Crisis: Polarization, Pandemic, Prejudice.”

PACON isn’t stopping there, either. In response to George Floyd’s murder in Minneapolis in the summer and the events that followed, the class will be, as co-teacher Jason Marsh put it, “beefing up our final module on BLM [Black Lives Matter].” A number of Conversation Programs will, likewise, bring discussion of racism, white supremacy, and Black lives into their virtual and hybrid classrooms.

Second-year AmConners are taking a deep dive into the Great Migration as the centerpiece of broader interdisciplinary studies that ask students to think about race and place and identity, including Ralph Ellison’s The Invisible Man, art, poetry, and the history of Chicago. New AmConners, whose first course is called American Stories, started with Frederick Douglass’s speech, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July” and are pivoting into a number of stories about native peoples, Latinx individuals, and Black people across the disciplines of film, autobiography, and history. In the case of both AmCon cohorts, student responses will be a combination of analytic and creative, individual and group work. See what I mean about new humanities? More work, a lot of juggling, but totally worth it.

When last year’s Asian Con group left China partway through Interim, COVID-19 hadn’t yet been declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization. This year Asian Con students can’t go abroad; their Interim has been deferred until January of 2022. In the meantime, Associate Professor of Asian Studies Ka Wong notes that the group has been talking about pandemic-inspired racism and stereotyping of Asians in the United States, adding further topicality to an already-topical program.

First-year Great Con instructors had to start forging a community virtually, taking special care in those early Zoom sessions to make sure everyone was heard and got to talk to other students. As some sections of Great Con are hybrid and others online, not all students can build community in the same way. Nor is community outside the classroom quite as possible right now. Thus, each instructor has evolved a strategy to ensure that students feel part of a more-complicated whole. Professor of Philosophy Jeanine Grenberg is “gently” nudging each student to speak during each class hour, for example, to get and keep people engaged. Doing so, I’ll remind you, requires some pretty dexterous Zoom teaching, but con profs have learned how to count students and keep mental lists afloat in their brains while posing questions about Chaucer or Freud or Zora Neale Hurston.

First-year AmCon instructors Associate Professor of Spanish Kristina Medina-Vilariño and Visiting Assistant Professor of History Christopher Elias were aware of the complications of the year from the start, the recognition that AmCon is “a program that is dedicated to helping students adjust to college life” at a time when there is not a whole lot of typicality to college life. Thus, they have stressed an ethic of care and emphasized “the importance of students leaning on others” — professionals, instructors, and one another. I heard that idea of human interrelatedness and collective responsibility echoed through all the Conversation Programs. It is, after all, part of what motivated their creation in the first place and the very definition of what it means to be a learning community.

Building such student-centered pedagogy is off to a great start for new members of both two-year programs — American Conversations and the Great Conversation — even as circumstances hamper community-building. The lesson, which I suspect we have all already discovered, is that you have to be more intentional about fostering shared responsibility and making sure everyone understands the ground rules of deep conversation. Eric Fure-Slocum has always launched his AmCon classes with a first-day conversation about conversing, something I hope a lot of you thought to take beyond the etiquette of Zooming (“mute your mics”) to matters of substance.

The lesson, which I suspect we have all already discovered, is that you have to be more intentional about fostering shared responsibility and making sure everyone understands the ground rules of deep conversation.

All Conversations Programs have a certain amount of social activities in them, which in the past have included everything from croquet games to live theater field trips. Without the ability to connect out of class, particularly early on, Science Conversation instructor Associate Professor of Philosophy Arthur Cunningham reports, “it’s not quite the same.” He, though, is happily enjoying a teaching situation other con programs might envy: his whole class can be accommodated in one classroom. Still, he started team building while the group was still virtual by dividing the class and giving them two models of the universe to explore, heliocentric and geocentric. By the time the class came together, masked and social-distanced, they still already knew what the bottom half of their Zoom collaborators faces looked like and had a clear sense of how the Science Conversation worked. Not surprisingly, Arthur reports that pandemic-related topics have emerged organically, entirely logical in a program that, and here I quote the program’s home page, considers the “complex interplay of science and society.” Something tells me that Science Conners are going to have a busy, relevant, and truly engaging year.

Second-year Great Con and Am Con instructors and their students have the advantage of already functioning as communities; however, as communities, they also suffered the traumas of last spring’s hasty shift to online. The instructors of second-year programs are aware of the scars and seek to use the shared experience of what Associate Professor of Religion Peder Jothen characterizes as the “bizarre spring” because we all have a “deep human need for social connection in order to feel fulfilled.” I believe that some of this fulfillment involves shared Harry Potter references, a familiar class touchstone that must feel great in its ordinariness.

It’s at the juncture of the bizarre, the desperately needed, and the ordinary Conversation Program stuff that Conversation Programs seem to be finding their centers. Their forever bonds might be a bit sadder and more serious than the T-shirts with inside jokes con cohorts seem to favor; still, like all cohorts, they will bond forever in ways that are deeper than your typical class might. Con programs this year might want to forego T-shirts and opt for con masks instead.

I hope that the promise of more work and more satisfaction gets you thinking that you want to join the sacred ranks of conners. To open a conversation about joining a Conversation Program, talk to one of the following:

- The Great Conversation — Professor of English Mary Trull

- American Conversations — Associate Professor of Spanish Kristina Medina-Vilariño

- Asian Conversations — Associate Professor of Asian Studies Ka Wong

- Public Affairs Conversation — Associate Professor of Philosophy Michael Fuerstein

- Science Conversation — Associate Professor of Philosophy Arthur Cunningham

- Environmental Conversations — Assistant Professor of Religion and Environmental Studies Kiara Jorgenson

All I can say is do it and you won’t regret it. Just ask your colleagues, people like Adjunct Assistant Professor of Writing Bridget Draxler ’05 or Visiting Assistant Professor of Classics Hilary Bouxsein ’09 (both Great Con alums, and Hilary valued the experience so much that she now teaches in the program), Web Developer Hawken Rives ’16 (AmCon AND Asian Con, the con overachiever), or Associate Dean of Fine Arts Recruitment Molly Boes Ganza ’08 and Associate Director of Marketing and Admissions Maggie Matson Larson ’08 (AmConners of, I believe, the same cohort). My apologies to the faculty and staff members I didn’t just mention who are also proud conversations alums. I’m confident there are more of you.

Perhaps it is fitting that as I’ve been writing this, I received an unsolicited email from a former student and enthusiastic AmConner, ESPN journalist Katie Barnes ’13, who sent me links to two articles they had written that were “much informed by my Humanities education at St. Olaf.” As a professor, that’s just about the greatest gift ever, giving meaning to what we all do. Meanwhile, I have watched a Facebook post among the AmCon 2004 cohort generate a lot of conversation and memories about course content, croquet matches, and T-shirts. Why am I not surprised that practically all of the cohort are Facebook friends so many years after they graduated? Once a conner, always a conner.

Judy Kutulas is a professor of history at St. Olaf College, where she teaches in the History Department and the American Studies program, along with American Conversations. She is the Boldt Family Distinguished Teaching Chair in the Humanities, charged with helping to revitalize humanities teaching and learning at the college. Read her inaugural ‘Adventures in the New Humanities’ blog post here.

Judy Kutulas is a professor of history at St. Olaf College, where she teaches in the History Department and the American Studies program, along with American Conversations. She is the Boldt Family Distinguished Teaching Chair in the Humanities, charged with helping to revitalize humanities teaching and learning at the college. Read her inaugural ‘Adventures in the New Humanities’ blog post here.