Ken Gonzales-Day: Shadowlands

September 1 – October 29, 2017

Ken Gonzales-Day: Shadowlands ran from September 1 to October 29, 2017 at Flaten Art Museum, St. Olaf College. The exhibition was curated by Christopher Atkins, then Curator of Exhibitions and Public Programs at the Minnesota Museum of American Art.

Ken Gonzales-Day is an interdisciplinary artist whose practice considers the historical construction of race. He supplements his photographs with research and writing that engage critically with history, art history, and Western conventions of race, blending historical tragedies with current events. Using photography and video, he explores trauma and resistance as experienced and embodied by racially oppressed populations in the U.S.

This exhibition is a concise survey of the artist’s career, including works from the Erased Lynching, Searching for California Hang Trees, and Run Up series. His most recent work draws parallels between historical lynchings and high profile cases of police brutality affecting communities of color today. The core of the Run Up series is a cinematic restaging of the 1920 lynching of Charles Valento. Utilizing details drawn from the coroner’s report and his own archival research, Gonzales-Day chose to focus on this particular event in order to draw attention to the police presence at the scene that tacitly condoned the extralegal violence.

A survey of Gonzales-Day’s work brings up one of his most poignant questions: What is the difference between collective resistance and racially motivated violence? It is a question being asked after recent tragic events in cities around the country, such as Ferguson and Los Angeles, as well as St. Paul and Minneapolis. By presenting historical occurrences in conjunction with contemporary events Gonzales-Day collapses the historical distance and exposes the unchanging reality of racialized violence in the United States. Exploring the dichotomy between presence and absence, Gonzales-Day draws attention to the selective vision of American history and the perception of people of color as expendable. He combines scholarly research and a photo-journalistic sensibility with rich aesthetics to create jarringly haunting portraits of historical trauma present in both the people and the land of the United States.

(click on an image below to enlarge it and see image details)

![The Lynching of "Spanish Charlie," Santa Rosa, CA [Inverted], 2016, Vinyl wallpaper](https://wp.stolaf.edu/flaten/files/2017/06/KGD_7-3-1024x676.jpg)

By presenting historical occurrences in conjunction with contemporary events, Gonzales-Day collapses time and exposes the persistence of racialized violence in America today.

![Untitled (Henry Weekes, Bust of an African Woman [based on a photographic image of Mary Seacole], 1859, and Jean-Baptiste Pigalle, Bust of Mm. Adelaide Julie Mirleau de Neuville, nee Garnier d'Isle), 2011](https://wp.stolaf.edu/flaten/files/2020/06/Artwork5.jpg)

Untitled (Henry Weekes, Bust of an African Woman [based on a photographic image of Mary Seacole], 1859, and Jean-Baptiste Pigalle, Bust of Mm. Adélaïde Julie Mirleau de Neuville, neé Garnier d’Isle from the John Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles), 2011

Chromogenic print

Gonzales-Day’s Profiled series began in 2004 with his research into physiognomy, a pseudo-science used by 19 th century doctors to justify racial hierarchies based on physiological differences that ascribed criminal behavior to people of color and indigenous people. The project also looks at how Enlightenment-era science measured the human form and the created ideals of beauty and otherness that persist today.

Mary Seacole was a Jamaican-born woman who aided English soldiers during The Crimean War and greatly contributed to the modernization of nursing in the nineteenth century. On the right, is a French Noblewoman. They are juxtaposed here to demonstrate the many features they share in common: curly hair, dimples, button noses. Rather than call out difference, this composition invites viewers to rethink their assumptions about race, whiteness, and how deeply engrained otherness is within western culture. On the impact of this work, Gonzales-Day has said, “Racial profiling, [or] discriminatory treatment of persons of color, remains at the center of political debates about criminal justice, terrorism, national security, and immigration reform despite the fact that scholars and scientists increasingly argue that race has more to do with culture than biology.”

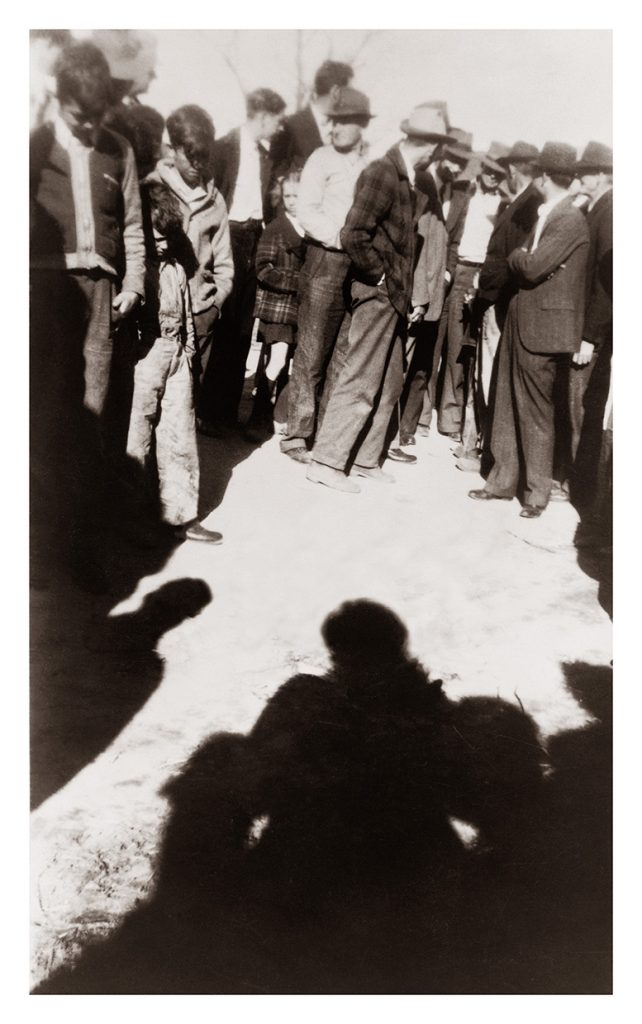

Erased Lynching, 2006

Chromogenic prints

As recently as the 1930s, photographs of lynching were printed in newspapers and onto postcards, mailed through the post office, and shared with family. They are a violent relic of American visual culture distributed using modern technology. The 15 photographs that you see here are based on lynching images Gonzales-Day found while writing his book Lynching in the West, available in our Reading Room. He has kept the intimate scale of each image intact but has carefully removed the hanged body using digital editing software. While he wanted to remind viewers of the historical tragedies, he did so without recreating the spectacle and re-victimizing the hanged person. What we are left with are the people who have perpetuated these crimes as well as a haunting reminder of how these bodies, up until recently, have been erased from the historical record.

Gonzales-Day describes how he uses the dichotomy of presence and absence to draw attention to the systems of oppression that made the violence permissible, “These absences or empty spaces become emblematic of a forgotten history – made all the more palpable in light of our expanding understanding of America’s history of lynching.” Lynchings are also paradoxically present and absent; we know they happened but even with extensive photographic documentation, the perpetrators were never indicted for their crimes.

Right: Sikeston, MO (Cleo Wright, from Erased Lynching Series II), 2013, Chromogenic print

Left: Waco, TX (Jesse Washington, from Erased Lynching Series II), 2014, Chromogenic print

Jesse Washington, a 17 year-old African American was lynched on May 15, 1926 in Waco, Texas. He worked as a farmhand for George and Lucy Fryer. While George was away, Jesse was accused of raping and killing Lucy Fryer. The sheriff arrested Jesse, and he allegedly confessed to and was then charged with murder. A huge crowd showed up for the trial, which lasted for just an hour. The jury deliberated for 4 minutes, finding him guilty of murder and sentencing him to death. Jesse was immediately taken out of the courtroom by a mob and hanged in front of more than 10,000 onlookers. His body was burned, mutilated, and parts were sold as souvenirs. The event, which became known as the “Waco horror,” was widely condemned throughout the country, and Washington’s death changed public opinion about lynching as an acceptable form of justice.

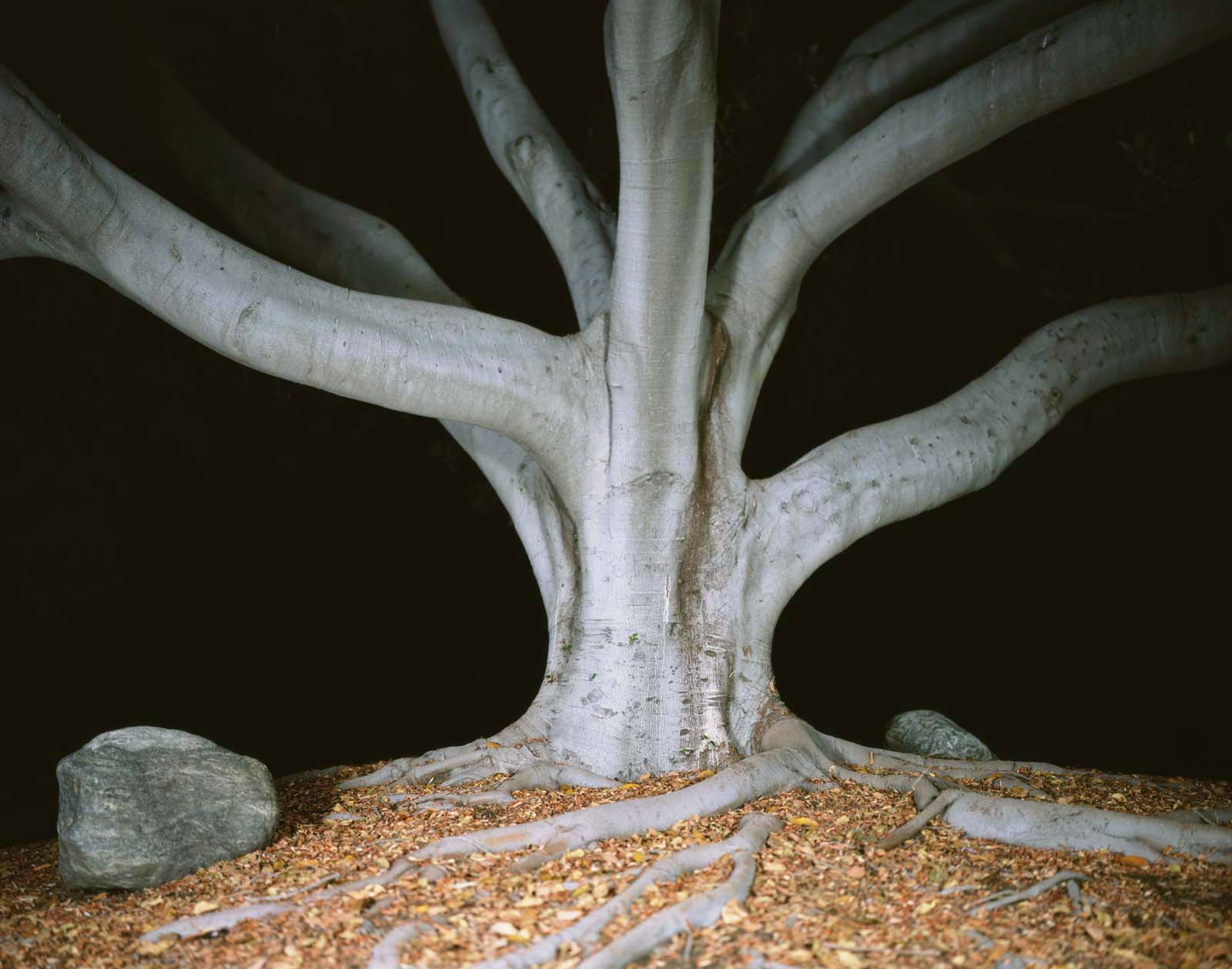

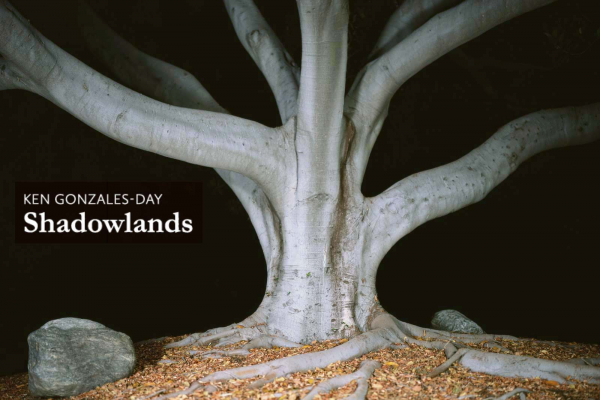

Nightfall I from Searching for California’s Hang Trees, 2007

Chromogenic print

The tall and majestic trees in Gonzales-Day’s Searching for California’s Hang Trees photographs stand as silent yet enduring memorials to the hangings that occurred. Living in plain sight, they are haunting reminders of the traumatic past that has seeped into the ground and how violence is rooted in the American landscape and our collective history. While they are photographed to accentuate California’s natural beauty, they show how these trees were bystanders to dark history as well.

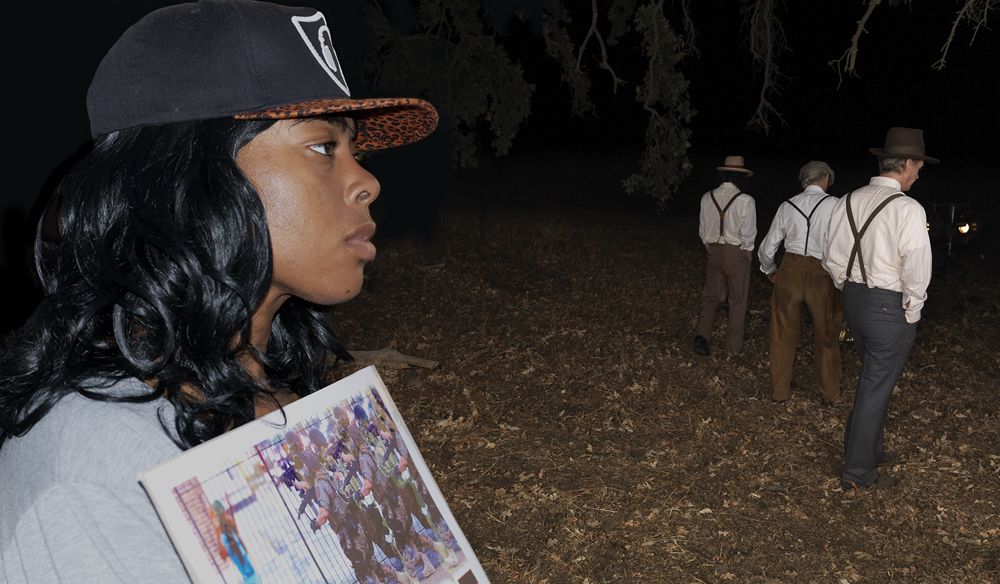

Gonzales-Day chose not show the moment Valento was hanged, and instead relies on the viewer’s imagination to fill in the blanks about the final moments of Valento’s life. What we see are the mob action, intoxicated judgment, and physiognomic pseudo-science that ultimately led to Valento’s death. These are the extra-judicial machinations that re-established Anglo-European dominance over American minorities, enabling this and other lynchings to occur.

![Still from Run Up [Movie], 2015](https://wp.stolaf.edu/flaten/files/2020/06/Artwork4.jpg)

Still from Run Up, 2015

Digital film

Far Left: Canfield Drive, Ferguson, MO, 2015, Chromogenic print

Top Right: Three Graces, 2015, Chromogenic print

The Graces are three minor goddesses from Greek mythology, most commonly Algaea (Splendor), Euphrosyne (Mirth), and Thalia (Good Cheer). They were often depicted in classical sculpture and then reinterpreted in Renaissance and Baroque paintings, most

famously by Raphael, Botticelli, Antonio Canova. Gonzales-Day’s photographs from the Run Up series, like this one, treat time as something fluid in which the past and present collide. These graces, clothed in 1920s era fashions and featured in Gonzales-Day’s reenactment of Charles Valento’s hanging, are shown here in present-day Los Angeles. They recall the crowds who opposed the riot-geared police officers holding their line during the November 2014 protests following the killing of Ezell Ford and Omar Abrego. Three Graces unwittingly foreshadowed other recent iconic photographs of women, such as Tess Apslund (Borlange, Sweden) and Ieshia Evans (Baton Rouge, Louisiana), who stood against white supremacists and police officers.

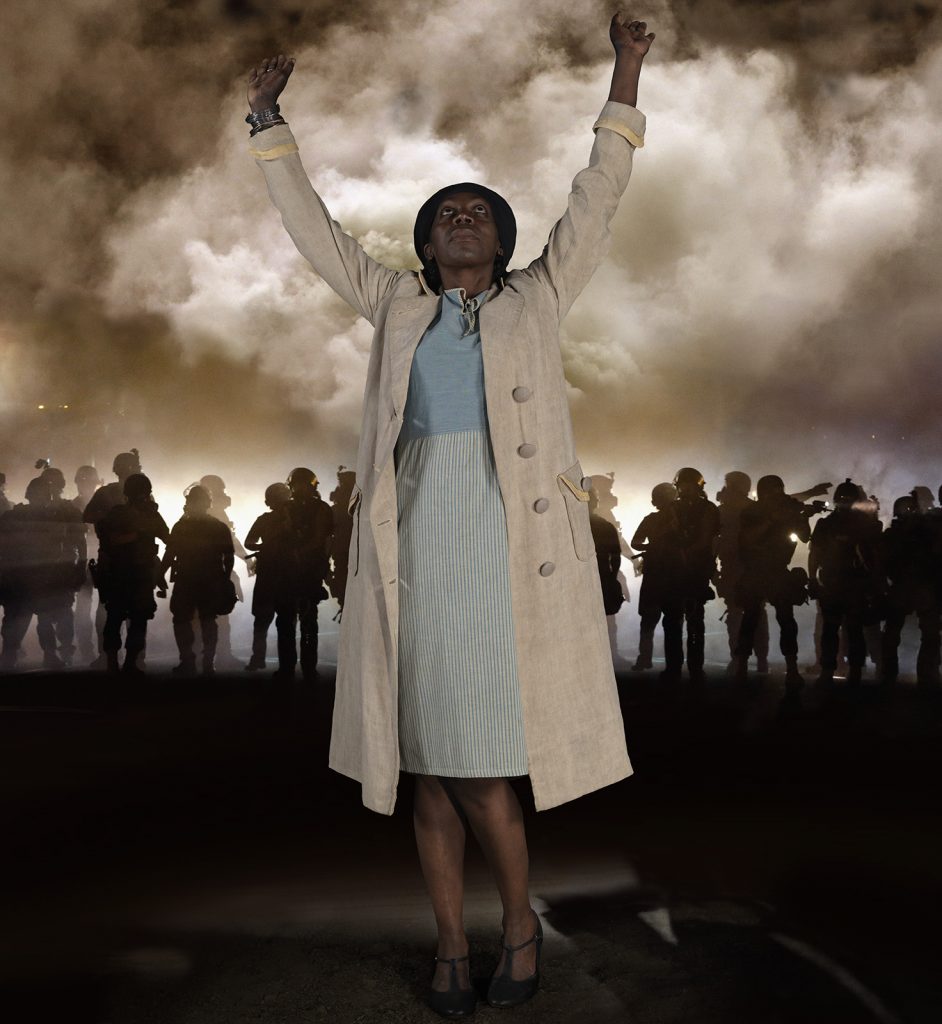

Middle: Hands Up, 2015, Chromogenic print

Bottom Right: Protester, 2015, Chromogenic print

Like the Three Graces and Hands Up photographs in this exhibition, Protester shows Gonzales-Day’s interest in compressing time in order to connect contemporary moments of racial violence with historical events. The woman on the left side was photographed at a demonstration after Ezell Ford, a young African American man, was killed by a Los Angeles police officer on August 11, 2014. The three men on the right side were part of Gonzales-Day’s reenactment of Charles Valento’s hanging which occurred in 1920. While the woman on the left looks towards them, the men have turned their faces and walk away without acknowledging her. This composite photograph speaks to the consistent yet unbridgeable rifts that are at the root of changing today’s racial tensions, eloquently echoed by James Baldwin:

You cannot lynch me and keep me in ghettos

without becoming something monstrous yourselves.

And furthermore, you give me a terrifying advantage:

you never had to look at me; I had to look at you.

I know more about you than you know about me.

Not everything that is faced can be changed,

but nothing can be changed until it is faced.

Canfield Drive, Ferguson, MO, 2015

Chromogenic print

This is the temporary memorial that sprung up in Ferguson, Missouri where Michael Brown was shot and killed by police officer Darren Wilson on August 9, 2014. Brown’s death ignited weeks of protests against the Ferguson Police force.

Gonzales-Day was taking photographs in Ferguson on January 7, 2015. Tensions remained hot despite freezing temperatures. The thin blanket of snow that covers the flowers and plush animals speaks to the persistence as well as the tenuousness of this memorial. These improvised memorials, which also appeared in the Twin Cities after the shooting of Jamar Clark and Philando Castille, serve as gathering places for community members to pay their respects, but are cleaned up after a time. If a permanent marker isn’t installed will anyone remember what happened here?

ARCHIVED EVENTS

Public Lecture: Seeing Minnesota’s Indigenous Histories, Ramona Stately

Wednesday, October 11, 2017, 3:30-4:30 p.m., Viking Theater

Responding to Ken Gonzales-Day: Shadowlands, Ramona Kitto Stately addressed how violences perpetrated against Minnesota’s indigenous community reverberate across time and through families and communities.

Public Lecture: Seeing Absence, Ken Gonzales-Day

Friday, October 20, 2017, 3:15–4:15 p.m., Viking Theater

In this lecture, Gonzales-Day explored his body of work and exhibition at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery.

Performance: Futuristic Moves

Thursday, September 21, 2017, 5–6 p.m.

This improvisational performance installation explored Black and Brown ancestral knowledge as a form of healing amidst collective practices of violence.

RELATED

The Reading Room

September 1 – October 29, 2017

The exhibition’s Reading Room, filled with books, poetry, and digital media that further explore themes around racialized violence in America, was a space for going deeper with the artwork of Ken Gonzales-Day and the issues it addressed; it was a quiet place to process, reflect, and offer a response.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Ken Gonzales-Day received a Painting (Art History minor) BFA at Pratt Institute and an MFA in photography at University California, Irvine. Gonzales-Day is a Professor of Art and Humanities at Scripps College. He has received many prestigious awards and museums fellowships, including the Terra Senior Fellow, Terra Foundation, Giverney, France; COLA Individual Artist Award, Los Angeles; Art Mattes Grant, New York City; Visiting Scholar/Artist-in-Residence, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles; Senior Fellow, American Art Museum and National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.; Fellow, Rockefeller Foundation Study and Conference Center, Bellagio, Italy; Van Lier Fellow, ISP, Whitney Museum of American Art.

His work also is in numerous permanent collections, including Smithsonian American Art Museum; Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney; Getty Research Institute; L’Ecole des beaux-arts, Paris; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Los Angeles County Art Commission; Eileen Harris Norton Foundation; and Norton Museum of Art.

Images courtesy of Luis De Jesus Gallery, Los Angeles

and Flaten Art Museum, St. Olaf College

This exhibition was generously supported by the Glen H. and Shirley Beito Gronlund Annual Exhibition Series Fund, St. Olaf College, and made possible by the voters of Minnesota through a Minnesota State Arts Board Operating Support grant and an Arts Access grant, thanks to a legislative appropriation from the arts and cultural heritage fund. This project was also supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts.

You must be logged in to post a comment.