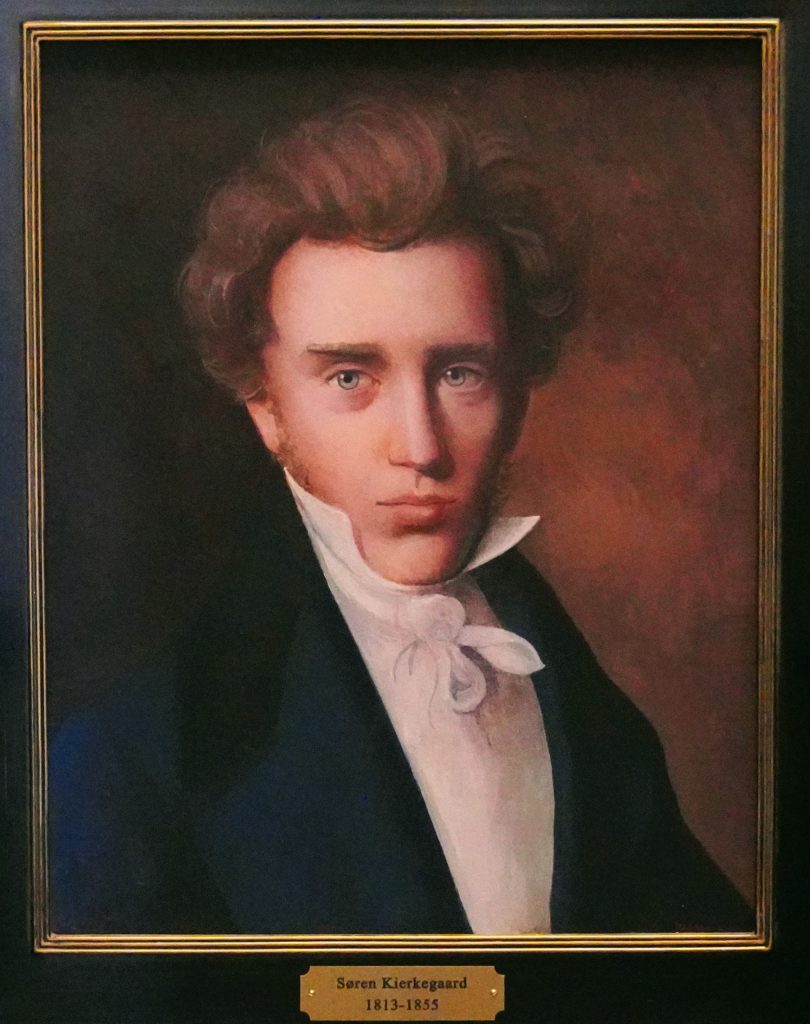

Here you will find resources to learn more about the Danish philosopher, Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855).

Kierkegaard’s Life and Writings

To learn more about Kierkegaard’s life and writings, visit these resources on the Søren Kierkegaard Centre website.

“Kierkegaard in Copenhagen: A Walking Tour”

Explore Kierkegaard’s Denmark from your home, or use this resource to lead an exploration in person throughout beautiful Copenhagen, as well as Northern Zealand.

Read this brief biography by Gordon Marino.